Does the museum have an ethical obligation to do the following? 1. Make the artist’s racist history, and apology, public at the show and in its publicity; 2. Allocate profits from the show to a program that benefits local Black artists; 3. Ask the artist to fund an art department in a historically Black college or university.

I think the museum may be wise to warn patrons that the content of the art is potentially offensive to people. They may also inform the viewers that the views and concepts expressed in the artwork may not reflect how the artist currently feels. They are a product of history, a sign of the times of when the artwork was created and based off of.

They may choose to provide as much additional context to the art as needed to ensure people are warned about what may be viewed as offensive these days. I see no reason to censor or soften the art though.

People do deserve the right of some content warning though; so that they may practice appropriate viewer discretion. Nobody needs their day ruined by unexpected racism, in a content context when they’re not mentally prepared for it, and informed of the historical context in which it was expressed.

If the art otherwise stands out and expresses a worthwhile message; I think racism can be safely ignored by a prepared viewer who understands that the racist messaging is not okay by modern standards and is willing to look past it to see the other themes in the art work. I don’t believe any museum of a respectable nature would present this art if it did not have some redeeming quality; as they’re typically concerned with preserving our history. Hiding the darker facets of our history, such as racism, from our descendants will only ensure that they repeat those mistakes.

As for points 2 and 3; I think this decision should be left up to the museum and the artist as a whole. I wouldn’t expect contributions to a charity to offset the harms; nor do I feel they would genuinely “offset” the racism in the art. Let the art stand alone, in it’s darkness and it’s light, separate from it’s artist and the museum presenting it. Judge the art alone.

It is okay to dislike an art piece but still have learned something from it; or to appreciate parts of it’s message but not others.

My local museum takes this approach with some of its historical exhibits, which were, to put it bluntly, stuff British soldiers nicked while they were in Africa, which were then donated to the museum when they died. These are all low value personal items which would be impossible to trace descendants of their original owners (its not practical to find the descendants of the owner of a shirt, a toy, a musical instrument, etc from 200 years ago), so instead the museum displays them with signage that puts them in the appropriate context for the time in history when they were acquired. As a result, I now know that a lot of men from my local area served in south Africa in the 19th century, who stole everything that wasn’t nailed down.

As a result, I now know that a lot of men from my local area served in south Africa in the 19th century, who stole everything that wasn’t nailed down.

Growing up going to museums this seemed to be a common occurrence. Theft and donations of artworks, which had been stolen at some point. For the art, I don’t mind as much as they were always pretty wild stories ranging from fires and recovery to theft and lost and refound – it’s like art heists where half of the history is what it’s gone through before it’s “final” resting place in the museum. But the personal items… those always hit different.

I think a really cool museum concept would be having contemporary cultures send in objects of their culture, because much like the little trinkets robbed back then, current little trinkets of today are just a bit different everywhere you go. We just don’t realize it until 10-20 years from now, or 100.

To add to this, I think it is important to keep in mind that what a museum or anybody else sees as a worthwhile message is very subjective. And through society’s biased lens this is often art by white cis men. Many of whom are seen as geniuses while being discriminatory or abusive to others, even in their message. But since the dominant culture is to only see these men as geniuses, their problematic behavior usually gets ignored. On the flipside, a lot of geniuses that aren’t white cis men are often completely left out and ignored. And this although their message is probably even more worthy of our attention because they actually experienced hardships that many white cis men never would have.

I don’t think it is a necessarily good idea to let museums have the choice alone what is a worthwhile message just because I don’t trust them to be reflective of the above. Museums should also be in dialogue with their community and what they deem worthwhile to present. (However this also opens the door to conservative bigots trying to prohibit anything remotely progressive.)

I’m not going to agree with you on this. I think it’s unfortunate that your focus is on the assumption that it’s a purely white and cis male dominated decision; without providing any evidence that the museum is run strictly by cis white men.

Furthermore, you focus on problematic behavior; which is important to document completely if we are trying to present that history in a complete and educational manner that allows us to avoid repeating past mistakes. There should be no room for censorship in education, because that’s how bigotry, racism and such will breed…in the shadows of ignorance that the censorship casts upon it’s recipients.

I’ve never said that any museum is strictly run by cis white men. My point is that the patriarchy and racism are real and lead to unconscious biases that we should be cautious of. Many museums have not done enough in being reflective of their own history and the history of the material they present (e.g. museums that present stolen artifacts from former colonies). I’ve never talked about censorship either, but rather getting a dialogue going between museums and their community. You projected a lot onto my comment there. Maybe you should think about what you’re defensive about here.

At best: careful and proper contextualization. At worst: a tasteful and respectful distance between “the transgression” and display for the sake of historical and educational review with possibly decades and dozens of people fighting acrimonious legal fights over absurd minutia to arrive at such decisions— or to never arrive at any at all.

The proper curation of anything can be very difficult. When it comes to controversial works, it can be almost impossible to get right sometimes, but it makes it so much worse when there are those determined to get it wrong.

I feel like there should be a line of intention. The artist described in the article was essentially racist by ignorance. She didn’t really know any Black folks, and fetishized them from afar. Doesn’t excuse her offense entirely, but perhaps ignorance mitigates her offense somewhat.

I was pleasantly surprised that Professor Appiah’s take was so nuanced.

Enjoy unlimited access for £2 a month your first 6 months.

🤖 I’m a bot that provides automatic summaries for articles:

Click here to see the summary

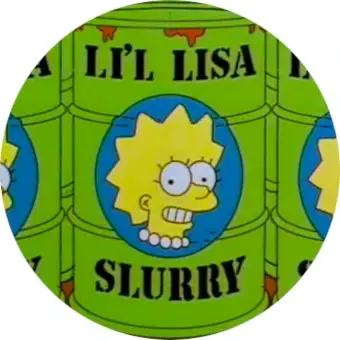

A lot of the book is about the orgies and antiwar “naked happenings” she staged, and she was intrigued by Black people as objects of desire, unabashedly exoticizing and eroticizing them.

And so, in the dramatis personae of one of her plays, the savage Black character is the one person who offers the heroine “the possibility of love.” But perhaps the main exhibit in the case against Kusama is a wild and surreal novella she published from the 1980s centered on a recent N.Y.U.

grad named Henry who, struggling with addiction, falls into the clutches of a Chinese woman, Yanni, and the escort service she runs for a rich gay clientele.

“Different readers make different readings,” as the scholar Kobena Mercer observed, in an influential essay that — discussing Jean Genet, Robert Mapplethorpe and Rotimi Fani-Kayode — interrogated “racial fetishism” as a catchall dismissal.

If the letter writer is a practicing Catholic who believes in the Church’s canon laws on marriage, he should not feel obligated to serve as his cousin’s witness for an annulment.

It’s been decades since I left the Church, but it seems to me that if the letter writer’s cousin is basing his annulment petition on false testimony from friends and relatives, his second marriage cannot be viewed as valid, either.

Saved 87% of original text.