Ok comrades, we have quite a bit done, we are well into our stride. Look at those fat juicy progress bars: while there is still a long way to go, remember how recently they were just a flimsy few pixels. Last week we left behind Dickensian factories and looked at the liminal space between master crasftsmen’s workshops and the drone-work on assembly lines. Now we are going to get into more detail on how that change happens, and how factory-work takes hold of society.

Don’t forget that this is a club: it is a shared activity. We engage with Karl Marx, and we also engage with each other in the comments and build camaraderie.

The overall plan is to read Volumes 1, 2, and 3 in one year. (Volume IV, often published under the title Theories of Surplus Value, will not be included in this particular reading club, but comrades are encouraged to do other solo and collaborative reading.) This bookclub will repeat yearly. The three volumes in a year works out to about 6½ pages a day for a year, 46⅔ pages a week.

I’ll post the readings at the start of each week and @mention anybody interested. Let me know if you want to be added or removed.

Just joining us? It’ll take you about 15-16 hours to catch up to where the group is. Use the archives below to help you.

Archives: Week 1 – Week 2 – Week 3 – Week 4 – Week 5 – Week 6 – Week 7

Week 8, Feb 19-25, we are reading from Volume 1: what remains of Chapter 14 (i.e. sections 3,4 and 5), plus section 1 of Chapter 15

In other words, aim to reach the heading ‘The Value Transferred by Machinery to the Product’ by Sunday

Discuss the week’s reading in the comments.

Use any translation/edition you like. Marxists.org has the Moore and Aveling translation in various file formats including epub and PDF: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/

Ben Fowkes translation, PDF: http://libgen.is/book/index.php?md5=9C4A100BD61BB2DB9BE26773E4DBC5D

AernaLingus says: I noticed that the linked copy of the Fowkes translation doesn’t have bookmarks, so I took the liberty of adding them myself. You can either download my version with the bookmarks added, or if you’re a bit paranoid (can’t blame ya) and don’t mind some light command line work you can use the same simple script that I did with my formatted plaintext bookmarks to take the PDF from libgen and add the bookmarks yourself.

Audiobook of Ben Fowkes translation, American accent, male, links are to alternative invidious instances: 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7 – 8 – 9

Resources

(These are not expected reading, these are here to help you if you so choose)

-

Harvey’s guide to reading it: https://www.davidharvey.org/media/Intro_A_Companion_to_Marxs_Capital.pdf

-

A University of Warwick guide to reading it: https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/english/currentstudents/postgraduate/masters/modules/worldlitworldsystems/hotr.marxs_capital.untilp72.pdf

-

Reading Capital with Comrades: A Liberation School podcast series - https://www.liberationschool.org/reading-capital-with-comrades-podcast/

We finally got to the Marxist module in my philosophy class and I feel in my element. I’m a little annoyed at how rusty when trying to re-read and understand Marx’s verbose prose.

How’s everyone appreciating the book so far?

Hate it. Absolutely zero character development.

empirically false! The owner of labour power and the owner of money developed into the capitalist and worker!

But have they made up, or are their struggles only going to increase from here?

Enemies to Lovers, slowburn, sharing a bed trope, mpreg

@invalidusernamelol@hexbear.net @Othello@hexbear.net @Pluto@hexbear.net @Lerios@hexbear.net @ComradeRat@hexbear.net @heartheartbreak@hexbear.net @Hohsia@hexbear.net @Kolibri@hexbear.net @star_wraith@hexbear.net @commiewithoutorgans@hexbear.net @Snackuleata@hexbear.net @TovarishTomato@hexbear.net @Erika3sis@hexbear.net @quarrk@hexbear.net @Parsani@hexbear.net @oscardejarjayes@hexbear.net @Beaver@hexbear.net @NoLeftLeftWhereILive@hexbear.net @LaBellaLotta@hexbear.net @professionalduster@hexbear.net @GaveUp@hexbear.net @Dirt_Owl@hexbear.net @Sasuke@hexbear.net @wheresmysurplusvalue@hexbear.net @seeking_perhaps@hexbear.net @boiledfrog@hexbear.net @gaust@hexbear.net @Wertheimer@hexbear.net @666PeaceKeepaGirl@hexbear.net @BountifulEggnog@hexbear.net @PerryBot4000@hexbear.net @PaulSmackage@hexbear.net @420blazeit69@hexbear.net @hexaflexagonbear@hexbear.net @glingorfel@hexbear.net @Palacegalleryratio@hexbear.net @ImOnADiet@lemmygrad.ml @RedWizard@lemmygrad.ml @RedWizard@hexbear.net @joaomarrom@hexbear.net @HeavenAndEarth@hexbear.net @impartial_fanboy@hexbear.net @bubbalu@hexbear.net @equinox@hexbear.net @SummerIsTooWarm@hexbear.net @Awoo@hexbear.net @DamarcusArt@lemmygrad.ml @SeventyTwoTrillion@hexbear.net @YearOfTheCommieDesktop@hexbear.net @asnailchosenatrandom@hexbear.net @Stpetergriffonsberg@hexbear.net @Melonius@hexbear.net @Jobasha@hexbear.net @ape@hexbear.net @Maoo@hexbear.net @Professional_Lurker@hexbear.net @featured@hexbear.net @IceWallowCum@hexbear.net @Doubledee@hexbear.net @Bioho@hexbear.net @SteamedHamberder@hexbear.net @Meh@hexbear.net

reporting in for posting duty

reporting in for posting dutyCapital drives increases labor exploitation by encouraging hyperspecialization let’s fucking go.

week 8!

week 8!Bruh I suck I haven’t read a bit of this even though I asked to be on this list 💀

You want me to remove you?

Maybe I can catch up by looking at some online summaries (if they exist)

Hey Comrade @Vampire@hexbear.net feel free to add my hexbear handle to this list as well (in edition to my lemmygrad handle). Thanks!

Ladies and gentlemen: We got him.

Ok, got it

Toward the end of last week’s reading, in chapter 13, Marx again traced an effect of the two-fold character of capitalist production, this time manifesting in the two-fold character of the control of the capitalist within the workplace.

[T]he connexion existing between their various labours appears to them, ideally, in the shape of a preconceived plan of the capitalist, and practically in the shape of the authority of the same capitalist, in the shape of the powerful will of another, who subjects their activity to his aims. If, then, the control of the capitalist is in substance two-fold by reason of the two-fold nature of the process of production itself, which, on the one hand, is a social process for producing use-values, on the other, a process for creating surplus-value; in form, that control is despotic.

I have been keeping note of these two-fold things since it helps me track which things are specifically capitalist and which might be inherent to production in general.

two-fold character of the control of the capitalist within the workplace.

Basically the owner & the manager.

which things are specifically capitalist and which might be inherent to production in general.

It took very close reading of the last passage to figure out was Marx saying is detail work specifically capitalist or inherent to large-scale production

two-fold character of the control of the capitalist within the workplace.

I read it as a direct correspondence to the value/use-value split. For producing use-value, the capitalist superintends the laborers, so as to organize their cooperation; to this end it is basically a good thing, a necessary aspect of cooperation in general. But because the capitalist also has in mind surplus-value, this superintendence takes on a “despotic” character, it spirals to ever greater intensity, because it is in the interest of the capitalist to push labor harder and harder without limit. The first aspect of organizing cooperative labor is natural, the latter aspect specific to capitalism.

Is this what you meant by owner & manager? The owner wants surplus-value, whereas the manager is focused on use-value, the technical work to be done?

“As co-operation extends its scale, this despotism develops the forms that are peculiar to it. Just as at first the capitalist is relieved from actual labour as soon as his capital has reached that minimum amount with which capitalist production, properly speaking, first begins, so now he hands over the work of direct and constant supervision of the individual workers and groups of workers to a special kind of wage-labourer”

There is where Marx starts talking about capitalist-as-manager.

As for capitalist-as-owner, well that’s been discussed at great length.

The manager and the owner can be the same person or different people. e.g. a shareholder or venture capitalist performs the functions of capitalists that we’ve seen at length (providing money for fixed and variable capital) but doesn’t do “the work of direct and constant supervision”. On the other hand, the guy who owns your local tyre shop probably runs it too.

“While division of labour in society at large, whether such division be brought about or not by exchange of commodities, is common to economic formations of society the most diverse, division of labour in the workshop, as practised by manufacture, is a special creation of the capitalist mode of production alone.”

Finally at the end of Ch.14 Sec.4 he makes it clear whether or not Manufaktur is capitalist or not.

Something I’ve been kicking around in my head a bit is the bourgeois notion of economic “efficiency,” which I feel like must mean efficiency at producing to meet the aggregate demands of society, which in turn are warped by the social inequities inherent in that society. We might then expect that as wealth inequality rises, an efficient free-market society will increasingly focus on producing luxury goods. (Which maybe can result in absolute immiseration if productivity increases in industries that meet basic needs do not offset their declining share of the economy? Idk I’d have to think more about this.) Anyway thought I’d throw this thought out there since Marx kinda touches on forces shaping the social division of labor in 14.4.

The way bourgeois economists talk about efficiency is annoyingly vague. It reminds me of how religious folks repeat empty phrases like “God is love” — it means whatever one wants it to think. It is a blank canvas for one’s own preconceptions.

Efficiency is a relative term, it is a comparison of the size of an output to the size of an input. But depending on which input/output one is talking about, it can be a different kind of efficiency. A Rube Goldberg machine is efficient in terms of human actions: simply pressing a button to start the machine is all the human must do in order to get the intended result. But it is obviously inefficient in terms of the complexity, materials, volume, noise, etc. Likewise, a car may be efficient in terms of CO2 per passenger, but inefficient in terms of volume per passenger.

When the bourgeois speak of efficiency, I think they most often mean efficiency in terms of capital. If the same absolute profit can be gained from a reduced capital advance, then that is an “efficiency gain.”

This talk of efficiency obfuscates the entire process of value production and reduces it to capital magnitudes alone. But it is the natural way for a bourgeois to think.

This kind of efficiency may be derived variously from reduction in waste (e.g. less sawdust, more saleable wood), a reduction in constant capital (e.g. cheaper machinery), or a reduction in living labor costs (e.g. layoffs + increased intensity of labor). Obviously this last point has a social element which is important to Marx.

Generalizing this idea of efficiency to the whole economy, the bourgeois would say: That economy is efficient which maximizes surplus value while minimizing the necessary capital advanced. The logical extreme of this would be an economy which can produce surplus value out of nothing, without even producing. The ideal economy is one which directly enriches the bourgeoisie and maintains their privilege to live off the labor of others.

For the latter, the cost of apprenticeship vanishes; for the former, it diminishes, compared with that required of the craftsman, owing to the simplification of the functions. In both cases the value of labour-power falls.

This is a key point: “manufacture” drives down wages and creates a class of uneducated workers.

Moses said: ‘Thou shalt not muzzle the ox when he treadeth out the corn’ [Deutoronomy 25:4]. But the Christian philanthropists of Germany fastened a wooden board round the necks of the serfs, whom they used as a motor power for grinding, in order to prevent them from putting flour into their mouths with their hands.

Marx’s footnotes are amazing (footnote 4 of ch15 is another good one)

I was thinking about a section in Michael Twitty’s “The Cooking Gene” where he compares the foodways and associated health of enslaved Africans in Tobacco and Cotton producing plantations.

Tobacco plantations in VA, the Carolinas, and the mid-South tended to have more diverse agriculture systems, and a portion of enslaved people were engaged in self-sufficient food production. For the horrors of slavery, the population was relatively healthy.

Cotton plantations were more “efficient” at producing the commodity, but the cotton was exchanged for non- perishable foods, themselves another commodity (Corn grits, molasses, and salt pork). Based on both historical and archaeological records, nutrition deficiency was rampant. The nature of the labor in producing cotton was both lower skill and took up longer days for a longer growing season.

All this saying, the “specialized” nature of labor can have serious health consequences, just like we saw with the examples of long work days.

Technically, globalization can solve this problem. People living in Chicago can go to the grocery store and buy oranges from Florida or coconuts from Indonesia. That’s why food deserts are so devastating: they deprive a portion of the population, almost always poor members of the working class, from access to proper nutrition - because there is no profit in maintaining their health.

“The same bourgeois consciousness which celebrates the division of labour in the workshop, the lifelong annexation of the worker to a partial operation, and his complete subjection to capital, as an organization of labour that increases its productive power, denounces with equal vigour every conscious attempt to control and regulate the process of production socially, as an inroad upon such sacred things as the rights of property, freedom and the self-determining ‘genius’ of the individual capitalist. It is very characteristic that the enthusiastic apologists of the factory system have nothing more damning to urge against a general organization of labour in society than that it would turn the whole of society into a factory.”

This is an important passage for understanding what Marxism would look like. Here Marx talks about the planned economy.

Capitalists do accept the ‘planned economy’, so long as it’s within the walls of a factory. And Marx has praised the division of labour as increasing productivity (especially in Ch.14 Section 2). So Marx wants to bring that increased productivity to the economy as a whole by bringing the same sort of rational planning into the economy as there is in the factory.

Yes, but Marx feels much more ambivalent on manufacture and division of labour and factories general than this.

Marx is not saying “factory organisation good” here; he is saying “the bourgeois admit factory organization is shit when it applies to them but pretend its great when it applies to the workers.”

Socialism will ofc have to seize onto existing(machine) manufacture just as capitalism originally seized onto handicraft, but eventually socialism will need to move beyond this factory-like division of labour and it is hence not something to be idealised or uncritically praised.

This is not a passage where Marx is outlining what crude communism will look like; this is a passage where he is calling out bourgeoisie ideologue hypocrisy.

Marx is not saying “factory organisation good” here;

I said above “Marx has praised the division of labour as increasing productivity (especially in Ch.14 Section 2).” Here’s some thing he said:

-

“it is firstly clear that a worker who performs the same simple operation for the whole of his life converts his body into the automatic, one-sided implement of that operation. Consequently, he takes less time in doing it than the craftsman who performs a whole series of operations in succession… Hence, in comparison with the independent handicraft, more is produced in less time, or in other words the productivity of labour is increased.”

-

“Manufacture, in fact, produces the skill of the specialized worker by reproducing and systematically driving to an extreme within the workshop the naturally developed differentiation which it found ready to hand in society.”

-

“A craftsman who performs the various partial operations in the production of a finished article one after the other must at one time change his place, at another time his tools. The transition from one operation to another interrupts the flow of his labour and creates gaps in his working day, so to speak. These close up when be is tied to the same operation the whole day long; they vanish in the same proportion as the changes in his work diminish.”

Section 3:

- “In comparison with a handicraft, productive power is gained, and this gain arises from the general co-operative character of manufacture.”

Marx isn’t praising productivity, especially not in the manufacture-division-of-labour.

Sections two and three describe manufacture, and sections four and five are harshly critical or condemnatory of it both in itself and as it exists under capitalism. This critique begins in section three, towards the end, when Marx talks about unskilled labour and the separation of activities which are rich in content from those which are tedious.

Section four has quotes like e.g.

This is not the place, however, for us to show how division of labour seizes upon, not only the economic, but every other sphere of society, and everywhere lays the foundation for that specialization, that development in a man of one single faculty at the expense of all others, which already caused Adam Ferguson, the master of Adam Smith, to exclaim: ‘We make a nation of Helots, and have no free citizens’.

Where Marx 1. quotes a bougie economist for extra authority on the division of labour sucking and 2. says that this (i.e. Capital) is not the place to discuss this in general. (For such discussion, see e.g. Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Law).

Section 5 is even more openly condemnatory e.g.

[Manufacture] converts the worker into a crippled monstrousity by furthering his particular skill in a forcing-house, through the suppression of a whole world of productive drives and inclinations, just as in the states of La Plata they butcher a whole beast for the sake of his hide or his tallow

P486-88 (Penguin Fowkes translation) also shows how, while the political economists view the social division of labour “as a means of producing more commodities with a given quanitity of labour, and consequently of cheapening commodities and accelerating the accumulation of capital”. He contrasts this view with that of the few modern economists who don’t fetishise exchange value, profit, etc, (as well as the ancients) where 1. division of labour allows people to do stuff they like and are good at and 2. without at least some division of labour nothing can be done.

I said above “Marx has praised the division of labour as increasing productivity (especially in Ch.14 Section 2).”

You also said:

This is an important passage for understanding what Marxism would look like. Here Marx talks about the planned economy.

Capitalists do accept the ‘planned economy’, so long as it’s within the walls of a factory. … So Marx wants to bring that increased productivity to the economy as a whole by bringing the same sort of rational planning into the economy as there is in the factory.

Which is the part i disagreed with

-

Also like, it is nice to see like Marx repeating himself or like, bringing back some stuff from like the beginning of the early chapters. kind of just like, bringing it all back more or less

Yeah, I’ve seen many complain about the repetitiveness of Capital, but all my pedagogical training and research (and personal experience) suggests repetition is just the best way to learn stuff. Marx seems very intentional with his repetitions, so I think he’s aware.

it’s really nice that Marx does! I like it when things are like constantly drilled

This is not the place, however, for us to show how division of labour seizes upon, not only the economics, but every sphere of society, and everywhere lays the foundation for that specialisation, that development in a man of one singular faculty at the expense of all others…"

p. 474 in my penguin edition

I’ve been reading a lot of jameson lately, and this is a point he repeatedly emphasises in his critique of postmodernism — how “postmodern” philosophers, in their rejection of grand narratives and totalizing theories, have completely failed to grasp the social reality produced by capitalism or something like that

That’s interesting. If it’s not too hard to find, do you have a book or article on that?

I do think this point is relevant to the increasing specialization in the sciences. Look no further than the separation of politics, economics, history, and sociology as independent areas of study.

Sure! Fredric Jameson’s Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1989) is probably the go-to book for a Marxist critique of postmodernism and the so-called ‘linguistic turn’ within Western philosophy (i.e. the obsession with text, sign, signifiers and so on). That, and maybe David Harvey’s The Condition of Postmodernity (1989).

For a more recent look at the state of academia, the introduction to Jason Josephson Storm’s Metamodernism: The Future of Theory (2021) gives a decent overview of some of the discourses and practices postmodernism has produced (like the separation within the sciences; the tendency to favor ‘micro’ histories over larger narratives; the distrust of reason/knowledge etc.)

I also recently came across this article from a didactics study that’s quite good (it summarizes some of the core arguments made by Jameson and other Marxist in the 90s):

"Brosio, A. Richard. 1994. “Postmodernism as the Cultural Skin of Late Capitalism: Educational Consequences..”

Some quotes from Brosio on the concept of totality:

Many postmodernist thinkers do not believe it is possible to employ intellectual activity to unmask oppression and injustice, partly because of their fear that all forms of inquiry merely refer persons from one authority to another, therefore adding to the perpetuation of authoritarianism. . . . How convenient this is to those who exercise real power.

One must add that writers in France and elsewhere in the West successfully have represented totalism as a dangerous Leftist concept that allegedly leads inevitably to the gulag, instead of as a description of global capitalism and its current hegemony that makes radical change seem not only unattractive to most but impossible because of the very nature of things

It would be fair to say that the consequence of giving up the concept of totalization is to repudiate the possibilities for theoretically informed collective action

Chapter 14 section 3, Marx notes how division of labor within manufacture mirrors (imperfectly) the larger division of labor between private producers. Thinking ahead a bit, it would seem that as producers expand production, the division of labor between private producers is replaced by a division of labor under a single capitalist as a monopoly. The progressive side to this, then, would be the possibility to replace the owner with a dictatorship of the proletariat, while retaining highly developed means of production.

Little question, there’s a paragraph in section 4 where he briefly says that New England is more dense than India, even though India is more dense in the way we usually mean the term because of the development of ‘means of communication.’ Is this basically just a way of talking about density in terms of socialized production? That’s how I took it, at least, because it seems like the way he talks about it he means to point out that the economy of New England is more interconnected, even if it has fewer people. Am I way off?

How many people can coöperate economically?

It’s no good having people just exist if they’re cut off by valleys or impassable jungle. They have to A) exist and B) interact (economically)

“it is a law, springing from the technical character of manufacture, that the minimum amount of capital which the capitalist must possess has to go on increasing.”

Some parts of section three reminded me of the reserve army of labor? Like when Marx was talking about glass being made. Like here

These five detail workers are so many special organs of a single working organism that acts only as a whole, and therefore can operate only by the direct co-operation of the whole five. The whole body is paralysed if but one of its members be wanting.

Also in section 5 with like the separation of science like here

It is completed in modern industry, which makes science a productive force distinct from labour and presses it into the service of capital

that part and the rest of that section, sort of reminded me of like, Mao and others emphasizing the importance of practice and not just only theory? I dunno why that part reminded me of that. Also that part in section 5 on like education with that G Garnier person reminded me of like, schools in the united states being defunded and stuff.

Also sec 1 of chapter 15, some of it reminded me of like, those robotic arms we have today in places.

glassmaking

Yeah such situations where even one worker missing causes the operation to stop is very related to the reserve army of labour, especially in “so-called unskilled” jobs (using marx’s definition of "jobs which don’t require lengthy apprenticeship), where if labour is lacking it is (sometimes literally) snatched up from the street. In more skilled jobs (which still have ‘apprenticeships’ but less lengthy; the trainee period is the modern apprenticeship) such as convenience-store clerk, capital has to pay and maintain labourers in excess of what is needed on average daily in case of firings, noshows, illnesses, etc. Capital of course vehemently resents needing to pay such “idlers” and aims to render them “redundant” by increasing penalties on noshows, forcing the ill to come to work, etc.

theory and practice

Thinking of Mao is apt and interesting, though this is more in the realm of practical Maoism (abolishing distinction between physical and mental labour) than theoretical, as science makes extensive use of practice. The big thing here however is the separation of theory from practice. The businessman theorizing about how to organize labour more efficiently doesn’t have to contort his body, speed his motions. He may not even see the results of his theories other than in spreadsheets showing “efficiency up, costs down”

Similarly, the scientist developing a new machine doesn’t have to worry about his fingers being cut off, about inhaling toxic fumes or mindnumbingly repeating the same task every thirty seconds. The more complicated, large, powerful the machine becomes (i.e., the greater the portion of capital that is constant capital), the more the working process (its character, its speed, its danger, its product, etcetc) of the worker is dictated to them by the machine designed by and for the “middle class”.

There’s more of a complete separation of theory from practice in whitecollar jobs from what I’ve heard though, hence all the “team-building” excercises, lengthy meetings and repeated silver bullets that “will totally fix education forever frfr” (all of which are ofc creators of makework jobs for the degree-holding class).

schools

This is a neat topic for Marx. I am not 100% sure, but next week or the week after we should see some mentions of the conditions of schooling in the factory schools. I imagine as the global north reproletarianizes more fully, the conditions in our schools will more closely resemble the ideal (i.e. Victorian) capitalist school systems. On a only slightly related note, standard/‘equal’ universal education is probably one of the two things Marx would tear the USSR, China, etc, apart on (he comes out strongly against universal education in critique of the gotha program).

robotic arms

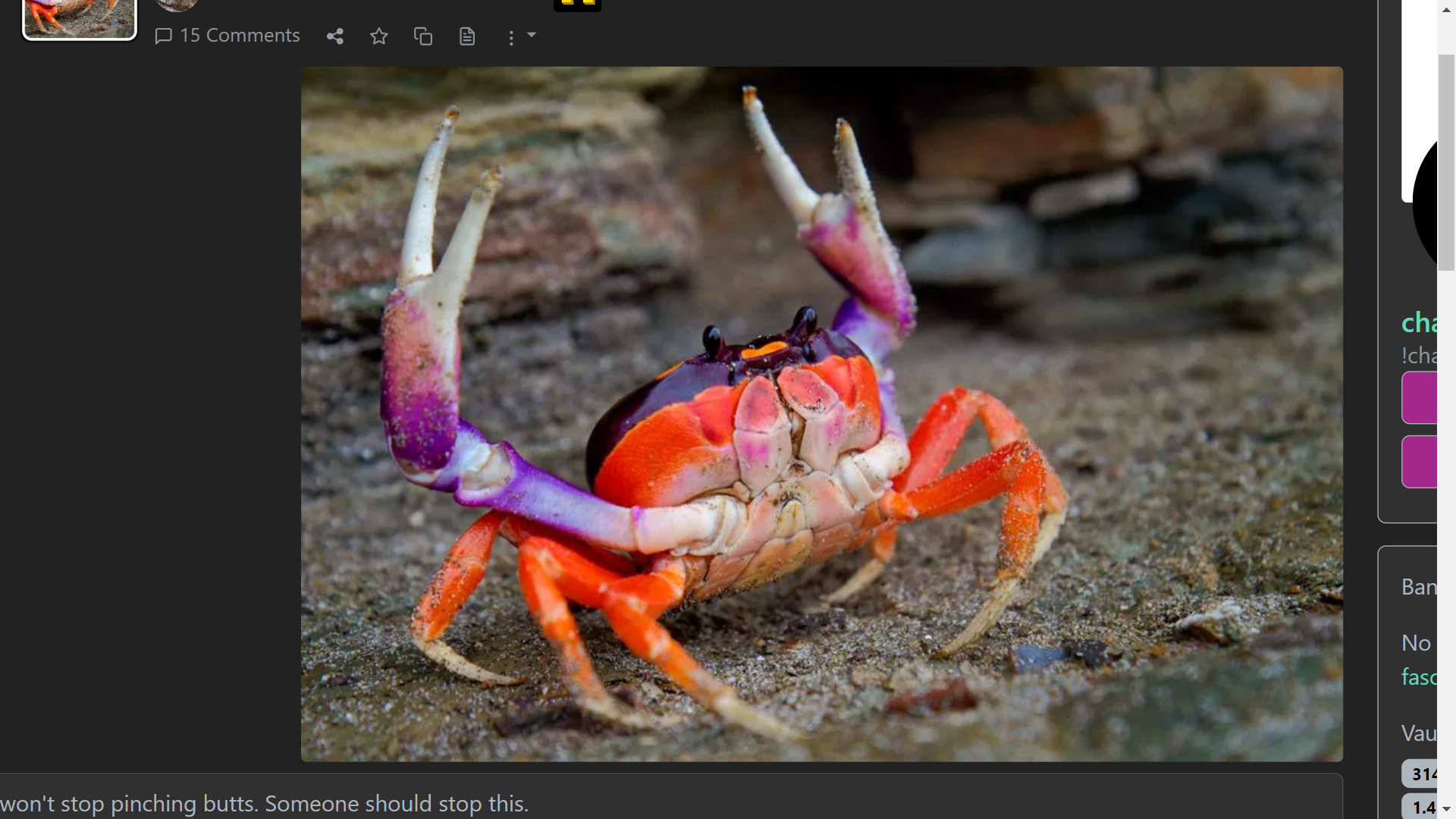

Yeah this is a perfect example of the thinking that gave us the steam horse locamotive @Sasuke@hexbear.net posted the picture of. Such arms are the starting point for creating more and more specific machines ofc

oh that further elaboration on separation of theory from practice was really interesting, and with the reserve army of labor, thanks!

On a only slightly related note, standard/‘equal’ universal education is probably one of the two things Marx would tear the USSR, China, etc, apart on (he comes out strongly against universal education in critique of the gotha program).

that surprising to learn, why was Marx against that? I really should go read the rest of the critique of the gotha program

So the Gotha Programme said: “The German Workers’ party demands as the intellectual and ethical basis of the state: 1. Universal and equal elementary education by the state. Universal compulsory school attendance. Free instruction.”

Marx says:

“Equal elementary education”? What idea lies behind these words? Is it believed that in present-day society (and it is only with this one has to deal) education can be equal for all classes? Or is it demanded that the upper classes also shall be compulsorily reduced to the modicum of education — the elementary school — that alone is compatible with the economic conditions not only of the wage-workers but of the peasants as well?

So his first issue is with both universally-equal and universal-elementary education.

Marx opposes universally-equal education because the present day society, unequal capitalist society, is unequal. The early stages of socialism / lower communism have to recognize this reality, recognize that perhaps peasants and wage-workers have different needs (“why do i need to learn X when I will likely stay a farmer?”) / abilities (hard to focus on abstract math when hungry) from the well-fed urban middle class, that access to teachers and instructions and supplies (etcetc) is very different from rural village to rural village. Equal education is either a falsehood or a reduction to universal elementary education.

Marx opposes universal elementary school because the elementary schools of the lower classes are shit, both today and in Marx’s time. It’s hard to comprehend from our modern viewpoint, but the “20-30 kids in a classroom one teacher who’s had maybe 4 years of rushed training” model of education is 1. recent, 2. horrible, 3. still miles better than the elementary education of Marx’s day. He would rather keep the current (i.e. unequal) education system and improve the elementary schooling as the material conditions of the workers, peasants, etc, improve.

Marx is also notably against free university and ambivalent on compulsory attendance and free elementary:

“Universal compulsory school attendance. Free instruction.” The former exists even in Germany, the second in Switzerland and in the United States in the case of elementary schools. If in some states of the latter country higher education institutions are also “free”, that only means in fact defraying the cost of education of the upper classes from the general tax receipts.

For Marx, free education is a way of the upper classes using general taxes to pay for the education of their managerial class, their scientists, their bureaucrats, their writers and artists, etc. Today we see for example university admission and graduation rates as well as who gets employed in their field varying by class, as nepotism is rampant in both, and inequality in terms of resources (housing, food, tutoring, etc) is still at play.

Instead of this universal education, Marx says:

This paragraph on the schools should at least have demanded technical schools (theoretical and practical) in combination with the elementary school.

I.e. “teach the children actually useful productive skills instead of abstract liberal education created by/for elites jerking off how good elite culture is”.

Marx also equally opposes state and church influence on schools:

“Elementary education by the state” is altogether objectionable. Defining by a general law the expenditures on the elementary schools, the qualifications of the teaching staff, the branches of instruction, etc., and, as is done in the United States, supervising the fulfillment of these legal specifications by state inspectors, is a very different thing from appointing the state as the educator of the people! Government and church should rather be equally excluded from any influence on the school. Particularly, indeed, in the Prusso-German Empire (and one should not take refuge in the rotten subterfuge that one is speaking of a “state of the future”; we have seen how matters stand in this respect) the state has need, on the contrary, of a very stern education by the people.

He’s fine with the state setting general guidelines, but otherwise he wants the government out of the schools, doesn’t want e.g. teachers to be state officials.

Marx’s stance on schools makes more sense when one knows that Marx opposes the abolition of child labour (my emphasis):

A general prohibition of child labor is incompatible with the existence of large-scale industry and hence an empty, pious wish. Its realization – if it were possible – would be reactionary, since, with a strict regulation of the working time according to the different age groups and other safety measures for the protection of children, an early combination of productive labor with education is one of the most potent means for the transformation of present-day society.

Rather than separating the parent-workers (still working 12 hour days and losing hands without pension) from their children, sending them into the hands of the state educators to be given a liberal education about how good liberalism is, Marx would see the conditions of working improved enough that it’s not horrible that children are working with their parents, because in working with their parents they gain a real education in what they’re most likely to be doing their entire life, a real education in what society is like. As above, Marx would like to see this supplemented with technical schools (theoretical and practical), but I get the sense Marx has little faith in liberal education (elementary or otherwise) as a result of his own experience and his daughters’ experiences with it.

oh! that does like, make a lot of sense. I can see like some of Marx’s points to. esp. since like things haven’t changed that much in today time. like that part about child labor sort of reminds me of like. parents needing to take time off from their work to pick up their children, if like they even could if their workplace allows them. and if like their children sick? and the parents can’t take a day off. that becomes like an issue? I know I almost like got my parents in legal trouble for missing a lot of school.

but thanks for writing that up, that was really good!

lmao y’all nerds still reading, how about you watch sports n drink beer 😂😘

I don’t watch sports.